|

How often do you see other patients and parents carrying their allergy medication in supermarket plastic bags, plastic boxes, the bottom of rucksacks or stuffed into handbags?

Considering millions of adrenaline auto-injectors are circulating worldwide, with an estimate of roughly one million in circulation, solely in the United Kingdom, the need for more education on allergy management is clear. Prescription allergy medication needs to be stored safely, in order to ensure its effectiveness. It’s clear that awareness is key when it comes to safely transporting allergy medication, and the best solution is continued and sustained training and information provided by healthcare professionals to carriers of allergy medication. So, are there really specific storage conditions and, if so, how do we know what they are? Let’s go back in time and try to understand adrenaline auto-injectors - the main medication needed in case of anaphylaxis. Although it’s now widely known that adrenaline is produced in the supra-renal glands of the human body, this was only found by a Japanese immigrant to the United States (Jokichi Takamine) in 1901. Before that, many studies had been done to understand why dogs who had their glands removed would eventually die. The research into what these glands were for started in the 16th century when they were discovered. Since Jokichi Takamine named the substance produced in them “adrenaline”, more research has been done to understand how it works and what led to it being more stable or degrading. Interestingly, it’s only since the late 20th century that we’ve had proper research showing the degradation of adrenaline when exposed to either sunlight or high temperatures. This research was focused on GPs carrying adrenaline in their bags in Pert, Western Australia. The evidence they had is that a Doctor’s black bag could reach temperatures as high as 80°C. So, let’s look at what the evidence has shown so far:

Understanding what the evidence shows is easy, but how should you weave this into your everyday life? The best and easiest way to do so is by carrying their medication in an insulated bag specifically designed to place it inside. Along with this, there are a few more steps needed to be taken, although they are relatively easy ones. Let’s make a short list of the “dos” and “don’ts” to keep your medication safe: DO:

DON’T:

If you follow those tips, you or your child can relax knowing that your medication is stored optimally. Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis/Pollen Allergy is most commonly known as hayfever and is triggered by a negative immune system response to grass, tree and plant pollen.

Hayfever symptoms usually present themselves in the spring and summer months, with different trees and plants reaching peak pollination at different times of the year. It’s important to know your triggers so you can take steps to minimise symptoms and protect yourself from pesky pollens. Pollen Allergy Symptoms Pollen allergy symptoms can be mild to severe, and may include the following:

When do UK trees pollinate? March Alder, Birch and Willow trees. April Ash, Sycamore, Oil Seedrape trees. May Oak and Pine trees. June Lime tree, grass and nettles. July Mugwort. Pollen Allergy Management In terms of medication, antihistamines are widely recommended to combat allergy symptoms and can be bought readily at pharmacies and supermarkets. These can be taken as a tablet, oral solution or a nasal spray. For those with more severe symptoms, an intranasal steroid spray may also be prescribed by your GP to help minimise discomfort and symptoms. More recently, balms which you can rub beneath your nose and around your nostrils and can be bought and used to help trap pollen before it enters your system. These mostly contain natural ingredients such as beeswax and have been received positively by those in the allergy community. Other steps you can take to help minimise symptoms include:

For information on the difference between Covid-19 symptoms and seasonal allergy symptoms, read more here. Adverse reactions to cow’s milk can occur at any age from birth, including in infants who are exclusively breastfed. It’s worth knowing that clinicians will often use the term ‘cow’s milk hypersensitivity’ to include some reactions that are not allergic.

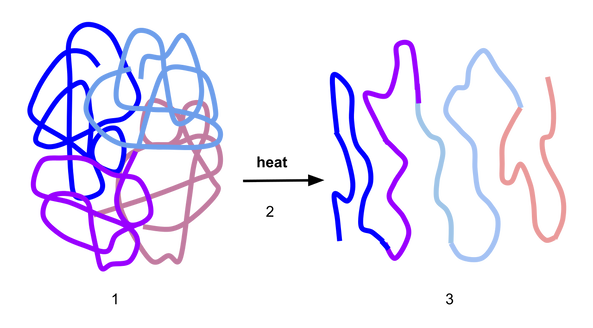

An allergic reaction to cow’s milk is a reproducible immune system-mediated reaction to one or more proteins in the milk. There are two types of allergic reactions; immediate, which occur 0–2 hours after consumption (IgE-mediated), and delayed, which occur from two to 48 hours later. It’s important to know what type of allergic reaction your infant or child has because this will define the investigations and the management plan. In terms of symptoms, infants can develop a sudden rash (urticaria), swelling (angioedema), projectile vomiting, refusing the breast or bottle just after they begin feeding, and exhibiting signs that they are in pain. Parents may see changes in the bowels with blood or mucous in the stools. Many infants become distressed and have sleepless nights crying. This is a stressful time that affects the whole family. If you suspect CMPA, see an allergy specialist as soon as possible. Some infants can develop eczema in the first few months of life, and this should not be mistaken for an allergic rash. However, an infant with eczema may also develop an allergy to cow’s milk and in this case, parents will notice an additional rash and eczema flare that may be difficult to control. This is also the case for infants with gastro-oesophageal reflux. They can have vomiting (non-projectile) after feeding and frequently exhibit pain, arching their backs after feeding and being unsettled. A detailed allergy history will guide your GP to make the right referral and begin treatment. When the medical history leads to the diagnosis of an immediate allergic reaction, a skin prick test or blood tests should be carried out. In cases where the allergic reaction is delayed, the diagnosis is made through the principle of elimination and re-introduction under the guidance of a dietitian which includes six weeks of avoidance followed by re-introduction. Breastfeeding mums can try to eliminate all milk and dairy from their diet for four weeks to see if the symptoms resolve. If avoidance is required, then Mum should receive Calcium and Vitamin D supplements. If there is still no sign of improvement, they should bring milk and dairy back to their diet as soon as possible. Some infants or toddlers can develop CMPA when they start weaning and are introduced to fresh cow’s milk. The symptoms are the same and a timely diagnosis and management plan are needed. The treatment is an avoidance of cow’s milk (fresh and in foods). Infants can receive a special formula that contains extensively hydrolysed milk proteins (e-HF). In some cases, only under the guidance of an allergy specialist, infants can be given an amino-acid formula (AAF) which is completely stripped of the proteins. It is not recommended for infants to start with this formula before trying the extensively hydrolysed formula first. Infants and children would require monitoring and in time, milk can be slowly re-introduced in their diet following a strict protocol. This is referred to as the milk ladder and should be designed and agreed with a specialist dietitian. Children and young people have a particularly good chance of growing out of their allergy to cow’s milk. This can be achieved with regular allergy tests and guidance from an allergy specialist and dietitian. Note: please do not mistake lactose intolerance with CMPA. Lactose intolerance is a non-allergic hypersensitivity. Children are still enjoying the summer holidays, but the schools are due to re-open their doors in September and I’m very conscious that I will soon be inundated with calls from concerned parents and letters from GPs or practice nurses with the same old question I get every year. “My child has an allergy to egg; can they have the flu vaccine?” and “this child needs a flu vaccine to be administered in a hospital due to having an egg allergy.” The fact is that there are very few individuals who cannot receive any influenza vaccine. The Department of Health guidelines state that none of the influenza vaccines should be given to those who have had: either a confirmed anaphylactic reaction to a previous dose of the vaccine, difficult to manage asthma, or a confirmed anaphylactic reaction to any component of the vaccine. So, if your child has none of these, then they can have their annual flu vaccine. If you are still concerned, talk to your GP. If an egg-free vaccine is not available, they should be able to advise you about a suitable vaccine with very low egg content. Sometimes, based on a child’s previous medical history, your GP may refer your child to the hospital to have a flu vaccine. This requires prior consultation with an allergy consultant and when appropriate, booking a day in the hospital where the child will be given a skin prick test. If the test is negative, part of the vaccine is given first and after a period of observation, the rest of the vaccine is administered. A little science: With egg allergy (as with all food allergies), we are concerned about the body’s mistaken immune response to the proteins in the egg which are: ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, ovomucoid, ovomucin and lysozyme. Ovalbumin is the major protein in egg white and it’s heat resistant - meaning that even when processed - sometimes egg still cannot be tolerated by individuals with egg allergy. Other egg proteins such as ovomucoid can be denatured by the heat. As a result, the shape of the protein changes (see the figure below) and increases the likelihood of tolerance. Inactivated influenza vaccines are egg-free or have extremely low ovalbumin content. For example, the Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccine (split virion, inactivated) manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur®, contains 0.12 micrograms/ml which is equivalent of a 0.05 microgram in 0.5 ml dose. Evidence shows that even LAIV manufactured by Fluenz Tetra® which previously had a higher content of ovalbumin of 1.2 micrograms/ml was also safe when given to children with egg allergy. LAIV now contains a significantly reduced ovalbumin content of a £ 0.024 microgram in a 0.2 ml dose. The Green Book is a document issued by the Department of Health about vaccines and every year, an update is issued about available vaccines and all relevant guidelines applicable to those vaccines. Your GP should have received their copy and will able to offer the best vaccine for your child. References:

1. Does food allergy cause eczema?

Eczema and allergy are two separate diseases. Eczema is a primary disease and food allergy does not cause eczema. Eczema usually presents itself in the first few months of life. Nevertheless, infants, toddlers and children with eczema can develop a food allergy too. As a result, if they consume the food they are allergic to, they will have a flare-up of their eczema. If you have concerns that some foods may cause a repeated flare of your child’s eczema (every time the child consumes the same food), then you may consider asking your GP to refer to an allergy specialist. 2. Can you test for everything so I can find what my child is allergic to? There is no global test for allergy that would tell us that. An allergy is a reproductive reaction to a specific protein in each type of food or environmental allergens. There are so many types of foods and aeroallergens which means it’s impossible to test them all. Instead, we take a detailed history to determine which tests to request. Therefore, your GP will ask you to keep an allergy symptom diary. An allergy diary is helpful to identify the trigger for your child’s reactions and establish an initial diagnosis. It is also useful background information for an allergy specialist. 3. Will my child grow out of their allergy? This depends on the age of the child when we identify the allergy and the type of allergen. When allergy is managed from infancy, some children will likely grow out of it. However, the type of food allergen is a key factor because the reaction is to a specific protein in the food and each food contains a different type of protein. Often, the proteins can be broken down by cooking or processing so the body can slowly accept it. This is often the case for milk and egg. When a small amount of milk is added to food e.g. a baked biscuit, some of the milk proteins are broken down by the heat. There is also a role which the other ingredients play - such as wheat - that also help the process. Introducing gradually small amounts of baked milk tends to be well accepted. The same principle is applied to egg, e.g. one egg added to a recipe for 12 mini muffins. The denatured egg proteins can be well accepted and define the beginning of a better tolerance to egg. However, with an allergy to fish and nuts, for example, heating or processing does not work and instead does exactly the opposite. Roasting nuts, even when mixed in food such as in pastries can make their protein stronger. Therefore, having a close working relationship with an allergy specialist and dietitian is important to ensure a safe and successful outcome. 4. My child has an allergy to egg. Can they have a flu vaccine? Children with an egg allergy may be at risk of an allergic reaction to the flu vaccine because most flu vaccines can contain part of egg protein (ovalbumin). This largely depends on the severity of your child’s allergy to egg and their history of an allergic reaction to other vaccines that may have a similar content (this can be established by your GP). In recent years, egg-free flu vaccines have become available and your GP can find the best option for your child. Sometimes, based on the previous history, your GP may refer your child to the hospital to have their vaccine. This, however, is not just a matter of coming and have the vaccine done. It requires consultation with an allergy consultant and when appropriate, booking a day admission on the ward where the child will have a skin prick test first. If the test is negative, then part of the vaccine is given first followed by the rest. With the fast-approaching new school year and autumn/winter seasons, I have written a more detailed blog post on the flu vaccine and egg allergy which you can read here. 5. My child has an allergy to egg; can they have an MMR vaccine? In 2009, the World Allergy Organisation issued the first memo to all clinicians, reminding them that measles and mumps vaccines are safe to be given to children with egg allergy without any special precautions. The vaccines are grown in chick embryo fibroblast and contain negligible or no egg protein. As with all vaccines, it should not be given to children who have had an allergic reaction to a previous MMR or suffered from anaphylaxis after a negligible amount of egg (e.g. a regular size cake containing one egg). We should remember that the risk of death from Measles is significant and therefore, your child having their MMR vaccine is important. If you have any concerns, seek advice from your GP who can refer you to an allergy specialist. While food allergies and intolerances can cause some of the same symptoms, there are some key differences between the two. These should help you differentiate between whether your child is suffering from a food allergy or an intolerance, but it’s always best to seek proper testing from a specialist for food allergies from if you suspect that might be the cause.

Digestive system vs. immune system response A food allergy is a negative immune system response to a food protein that triggers an allergic reaction. When an allergy occurs, your immune system overreacts, producing Immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies which travel to cells and release chemicals that cause an allergic reaction. 90% of all food allergies are caused by the top-eight food allergens, which includes wheat, soy, shellfish, fish, milk, eggs, soy, peanuts and tree nuts. The other 10% of food allergies can come from any food, with some children allergic to products such as red meat, citrus and celery (for example). Food intolerance, on the other hand, is a negative reaction to a food that doesn’t involve the immune system and instead takes place in the digestive system. Food intolerances are not normally life-threatening. Intolerance reactions normally take much longer to develop (up to 20 hours after consuming food) and occur when your body is unable to digest a certain food properly. Food allergy symptoms vs. food intolerance symptoms A food allergy can cause a potentially life-threatening reaction when the food is touched, eaten or even inhaled. This is referred to as anaphylaxis which normally occurs within seconds or minutes of eating food and symptoms include difficulty breathing, dizziness or losing consciousness. Anaphylaxis requires immediate treatment with an adrenaline shot to prevent fatal consequences, and the symptoms include suddenly feeling weak due to a drop in blood pressure and breathing problems as the throat begins to swell up. Other, nonlife-threatening symptoms of food allergy are either shown on the skin, respiratory or gastrointestinal. The most common symptoms of food allergy include itching, developing a rash or hives. Gastrointestinal symptoms are identified by vomiting or diarrhoea and respiratory symptoms can include shallow breathing, wheezing, chest congestion, coughing, a runny or blocked nose and itchy/watery eyes. In contrast to food allergies, food intolerance symptoms are focused on the digestive system and common symptoms include diarrhoea, bloating and an upset stomach. Less common food intolerance symptoms include weight loss, lack of energy, headaches and anaemia. These symptoms are often linked to other digestive disorders such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS and Chron’s Disease). Food allergy testing vs. food intolerance testing Food allergy testing can be carried out by an allergy specialist and there are two different ways to test for an allergy. For symptoms that develop quickly (an IgE-mediated food allergy) – a skin prick test or a blood test is the recommended tool for diagnosis. For symptoms that are slowed to develop (a none IgE-mediated food allergy) – a food elimination diet is the best way to diagnose. There are no food intolerance tests that are currently recommended by the British Dietetic Association, so the best way to identify an intolerance is to keep a food diary and monitor your symptoms. If you suspect a certain food is a cause, cut this out of your diet and see whether your symptoms disappear. You can then slowly reintroduce it to see if this causes your symptoms to flare up again. For advice relating to food allergies or intolerances, email me at [email protected] with any questions and I’ll be happy to help. The difference between allergy symptoms and covid-19 symptoms

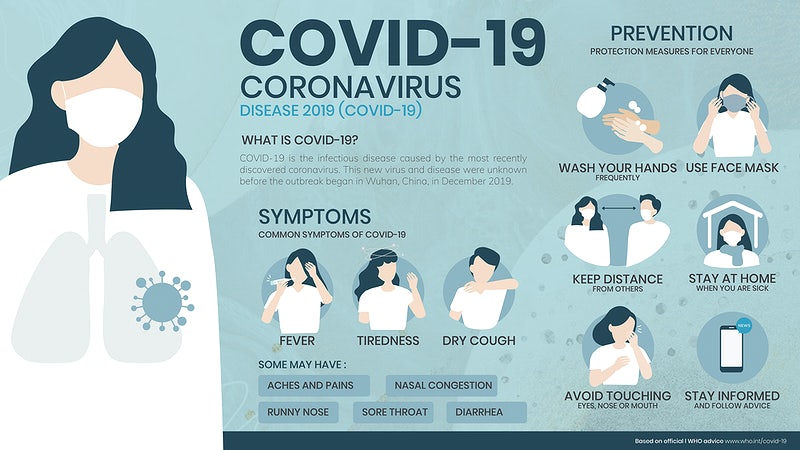

The coronavirus has heighted everyone’s fears when it comes to identifying symptoms – even if these are symptoms that have been experienced previously. The timing of the global covid-19 pandemic has also coincided with the onset of spring which is when many seasonal allergies begin to flare. To help put your mind at ease, we want to help highlight the differences between covid-19 symptoms and the symptoms associated with seasonal or year-round allergies. Covid-19 symptoms Covid-19 symptoms can appear up to two weeks after exposure, and the official symptoms include having a new, continuous cough, presenting a high temperature, physical fatigue and a loss or change to your sense of taste or smell. Although these are the main symptoms, other, less common symptoms have also been reported by coronavirus patients. These lesser-known symptoms include having a fever, sore throat or achiness. Some people have also reported sneezing, digestive issues/discomfort, mental fatigue, chills, nausea and diarrhoea. Seasonal allergy symptoms The key difference between Covid-19 symptoms and the symptoms of seasonal allergies are that you don’t normally get a fever and high temperature if you’re affected by an allergy. The symptoms of seasonal allergy are much more likely to include postnasal drainage, ear congestion, a runny nose and itchiness in various places - such as the eyes, ears, nose and throat. These symptoms are not known to be associated or reported as a symptom of coronavirus. Sneezing is another symptom that sets coronavirus and seasonal allergies apart. If you are just sneezing and do not have a fever or any achiness in the body – it’s most likely to be hayfever that you’re suffering from. Seasonal allergies also cause a non-stop sneeze and irritation, rather than infrequent sneezing which could be a side effect of coronavirus. You will likely see an improvement in your allergy symptoms after taking an antihistamine, so this will be a good indicator that your seasonal allergy has flared up. It’s important to remember that even though you have seasonal allergies, you could still be at risk of catching coronavirus, so should take all the necessary precautions when you’re out and about. Tips to help minimise the risk of catching coronavirus To help keep both your seasonal allergies and coronavirus at bay, you should continue taking your regular, daily allergy medication consistently. If you need to sneeze in public, you should do this as safely as possible, sneezing into a tissue or the corner of your elbow. Current NHS guidelines (on the day of publishing this article) recommend that you stay at home as much as possible, work at home if you can and keep a 2m distance from people when you’re out. For advice on your seasonal allergy symptoms, please email me at [email protected] |

AuthorAneta Ivanova Archives

March 2023

Categories |

The Consulting Rooms, 38 Harborne Road, Birmingham, B15 3EB

[email protected]

Website design & content by LIT Communication: www.litcommunication.com

[email protected]

Website design & content by LIT Communication: www.litcommunication.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed